From inside the global dismay on the subject of migration, continually associated with the deep wounds of terrorism to which we find ourselves more vulnerable every hour, emerges the latest urgency to start again from education: an idea and a proposal from AVSI Secretary General.

by Giampaolo Silvestri, secretary general AVSI Foundation, Corriere della Sera, July 25th

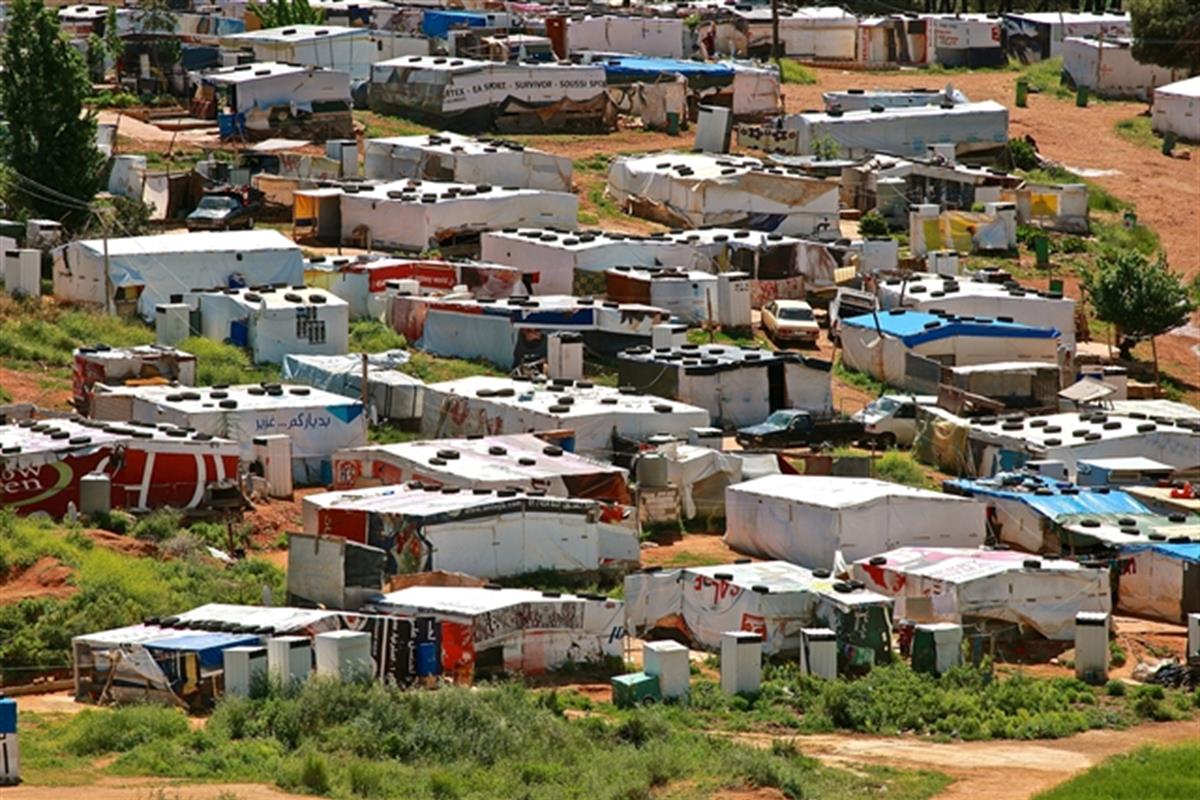

They go from house to house, tent to tent, to the last isolated villages in the Lebanese countryside, the educators who seek to return to school those Syrian refugee children living with their families in Lebanon. They talk to the parents, too often frightened, and they try to convince them that, even in emergency situations, it is possible, moreover, it's fundamental, that their children go to school. They learn to read and write, but most of all to be together, to discover the feeling of belonging to a community.

This came from Rana Najib, a Syrian woman who manages AVSI's educational projects, co-financed by UNICEF, in Lebanon, at a UN hearing in view of the summit in September on the subject of migrants and refugees, and she has made an impact. Because from inside the global dismay on the subject of migration, continually associated with the deep wounds of terrorism to which we find ourselves more vulnerable every hour, emerges the latest urgency to start again from education.

It's not a recipe for immediate success, but a long term investment. And also from sub-Saharan Africa to the Middle East, you can see with your own eyes how this challenging and decisive environment is for those who can see a bit further than the immediate.

However, the question is what kind of education is needed. Because it's not enough to concentrate on guaranteeing serious programmes, competent [teaching], and adequate stationery… Even ISIS and other violent extremists have their schools, and they are very well prepared. They obtain very high results from their students who go on to kill and kill themselves “for the cause”.

Why? Because in the end, with their radical proposals, terrorists seem to respond to the need for good reasons for which to give the life that is felt by every boy and girl of our time and of every continent, whether knowingly or not, whether they are unruly or have mental health issues. And if, in an age in which both Western and Islamic cultures appear marked by a deep crisis, this radicality implies the use of arms, it doesn't matter. Nothing stops.

To take this need seriously, alternative educational proposals are starting in Kenya and Lebanon, to quote just two cases among many. At Dadaab, a place where around 400,000 Somali refugees are living and from where the group behind the Garissa massacre was enlisted, or among the Syrian teenagers waiting for an ever more elusive peace.

At Dadaab, some educational and recreational groups have been started that are inspired by the Scouting movement: within a short space of time, the proposal involved hundreds of kids who, after sampling the feeling of belonging to an open, dynamic, and constructive community, turned their backs on the violent option. They found, having experienced being part of something, that their neighbor, even if they come from another city, if they attend another mosque or church, if they speak another language, if they have different customs, isn't an obstacle to overcome, but is a possibility of growth. That being different from me isn't a problem, but an opportunity to build something good for me and for the entire community.

In Lebanon, you will find sitting at the same school desks and playing together, Syrian, Sunni, and Shiite children. In the first place, they are guided to discover that those who live in an “enemy” city don't have to be an enemy. But this doesn't get “taught” by words, they experience it. And that experience stays with you. An experience of belonging that, like everything good, is infectious and can disarm.