Jo Griffin in Belo Horizonte. Photograph Gustavo Oliveira - The Guardian

Renato Da Silva Junior harbours ambitions of becoming a lawyer. There is just one obstacle: he is a quarter of the way through serving a 20-year jail sentence for murder.

“My dreams are bigger than my mistakes,” says Da Silva, a slightly built man with a broad smile. “I am doing everything to get out of here as soon as I can.”

Da Silva, 28, an inmate at the men’s prison in Itaúna, a town in Minas Gerais, south-east Brazil, is chipping away at his sentence and has already reduced it by two years through work and study at the Association for Protection and Assistance to Convicts (Apac) prison. Here, inmates wear their own clothes, prepare their own food and are even in charge of security. At an Apac jail, there are no guards or weapons, and inmates literally hold the keys.

A visit to the Apac men’s and women’s prisons in Itaúna subverts all expectations about the penal system in Brazil, where overcrowding, squalor and gang rivalry regularly cause deadly riots. These widely reported outbreaks are one reason Brazil’s penitentiaries are often regarded as a ticking timebomb where inmates languish in inhumane conditions with little chance of rehabilitation. Brazil has the world’s fourth largest prison population.

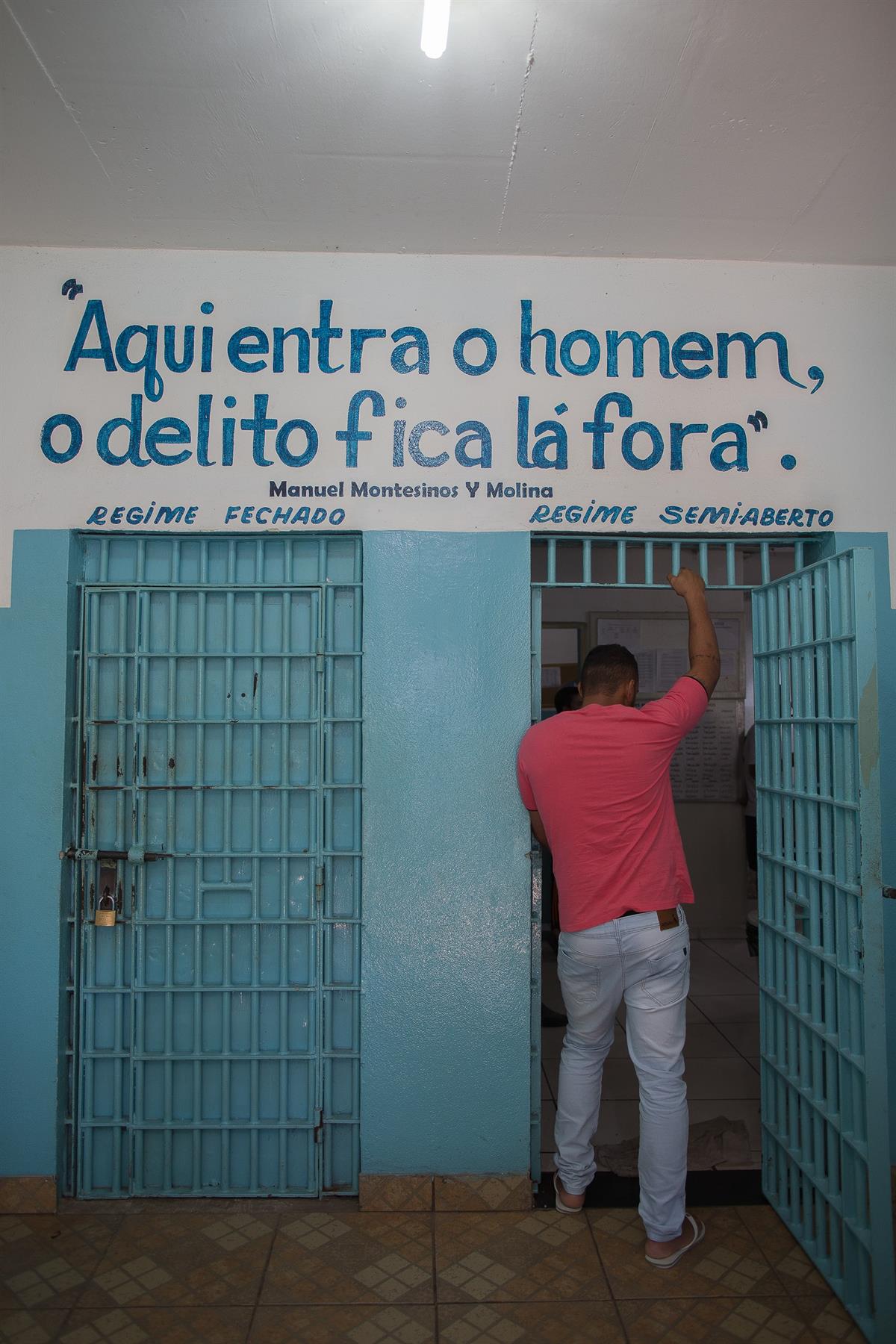

In Itaúna, the main door of the men’s jail is opened by David Rodrigues de Oliveira, a recuperando or “recovering person”, as inmates are known in the Apac system. This word is displayed alongside his name on a lanyard that also states his category of regime: closed, semi-open or open. In contrast with mainstream prisons, Apac inmates are addressed by name rather than number.

“I have no thought of escaping. I’m near the end and have almost paid for my crime. They put their trust in me and it’s my responsibility to guard the door,” says Da Oliveira, 32. “My next step is conditional release, where I can go out once a week. I have my family to think of. I wouldn’t jeopardise that.”

Another reason inmates uphold the strict routine of work and study required by Apac – under which no one is permitted to stay in their cells unless they are sick or being punished – is that an escape attempt would return them to the mainstream system, which all inmates have experienced before.

No detail of the contrasting regimes escapes the inmates. “Here we eat with metal knives and forks, while there we are given plastic, as if we are not human beings,” says recuperando Luiz Fernando Estevez Da Silva. “It’s not only the criminal who goes to jail, it’s his family. There, relatives who visit are strip-searched.”

Twenty or more people crammed in a cell, filthy mattresses and inedible food are common complaints in mainstream prisons. Apac prisons, coordinated and supported by the Italian AVSI Foundation, impose a limit of 200 inmates to prevent overcrowding. New arrivals come with shoulders bowed and hands behind their backs, says Da Silva, and they first have to learn not to stare at the floor.

Founded in 1972 by evangelical Christians to provide a humanising alternative to mainstream prisons, the system has now reached 49 jails in Brazil, and has branches in Costa Rica, Chile and Ecuador. They seek to rehabilitate inmates, who must show remorse. They are cheaper to run, have lower rates of recidivism, and are designed to benefit the wider community.

Ana Paula Pellegrino, of the Igarape Institute thinktank in Rio de Janeiro, says: “By committing a crime, prisoners break the social pact. An Apac prison restores this by allowing inmates to work for the community. Some prisoners might go out to sweep the streets, for example, which gives them a sense of responsibility and belonging.”

In the semi-open section of the prison, Rodrigo de Oliveiro Pinto, 35, enjoys the quiet job of running the storeroom, where a poetry book is open on his desk. De Pinto has 12 years to serve for murder. He wants to work in an Apac after release.

My head was messed up and I got into trouble. Coming here changed me. I want to come back to help others

Rodrigo de Oliveiro Pinto

In the closed area, the Apac philosophy is written on the wall, with slogans including: “The man enters, the crime stays outside.” Prisoners convicted of the most heinous crimes are here, yet it feels calm and safe.

In the woodwork room, the mood feels darker. “This area is for the new arrivals,” says Jacopo Sabatiello, vice-president of AVSI Brazil. “They have broken something with their hands so now they must make something good with their hands. When they go to the semi-open area they will do work that gets outside, past the door.”

In the garden behind the building, Renato Diego Da Souza, 31, is sticking labels on bottles for soap, to be sold outside. Prisoners also bake bread for local schools and produce plastic car parts. Da Souza says his problems began with drugs, which led him into armed robbery. But there is light at the end of the tunnel after his recent transfer to the semi-open regime. The chance of moving between regimes is a constant topic for the recuperandos. In mainstream prisons, tens of thousands are detained, sometimes for years, before their cases even go to trial.

Apacs are an effective way to respect human rights within Brazil’s penitential system, says Judge Paulo Antônio de Carvalho. “I’m in no doubt that prisoners’ individuality and fundamental rights as guaranteed by the constitution are respected … a prisoner should only lose his liberty, but keep his fundamental rights.”

It is a sad reflection on the mainstream system that Apacs are praised for upholding the law in a judicial system that unfairly dishes out tougher sentences to certain sections of society, mainly poor, black people, De Carvalho says.

With such a successful track record, why aren’t there more Apacs? “Every time there is another prison riot in Brazil, someone gets the phone to say they want to open an Apac in that area,” says Sabatiello. “But opening an Apac requires several things, including involvement of the state [where it is located] and political will.”

Financial problems, overcrowding and corruption have bedevilled efforts to open an Apac in Rio. These are typical hurdles.

Across town, in the open section of at the Apac women’s prison, inmate Aguimara Campos, 30, explains her role as president of the eight-member council of sincerity and solidarity, which organises some aspects of prison life and is a bridge with the administration. Sitting at a table in a sunny patio where women are making handicrafts, she describes how different her prison life used to be.

She was convicted of trafficking and association after 26g of crack cocaine was found in her house. “I knew nothing about the criminal life and was thrown in a cell with 29 other women, sleeping on mattresses on the floor. The woman next to me had decapitated her neighbour and had carried the head around in a bag.”

Tatiane Correia de Lima, a 26-year-old mother of two who holds the keys to the closed section, says moving to an Apac has restored her femininity. “The other prisons take away your womanhood. We weren’t allowed proper mirrors. When I saw my reflection here, at first I didn’t know who I was.

Reporting for this article was made possible by a residency at Casa Pública provided by Agência Pública